How climate uncertainty impacts crop yield

August 5th 2021

As harvest approaches, farmers and agronomists eagerly assess their crops to try and anticipate how crops will yield. Yield estimates are important to inform forward selling of grain, plan storage, and update budgets. Of course, there are many factors that influence yield including management regimes and soil types but all of these factors are heavily influenced by the weather.

Weather is the determined by the day-to-day state of the atmosphere and is derived from a combination of temperature, humidity, precipitation, cloudiness and wind. Whereas, climate is the prevailing weather conditions of a region over a long period of time. On a seasonal basis, the UK is experiencing more extreme weather conditions which are impacting the yield and quality of crops grown.

Farmers and agronomists have to deal with ever increasing uncertainty of predicting, on an annual basis, how the fluctuating weather conditions will impact the growth of crops. The cumulation of these changes year on year are now recognised to have altered and the whole of the world is known to be impacted by climate change. Current and future cropping systems are going to be challenged by growing in increasing CO2 concentrations and temperatures, decreasing water availability, and an increasing frequency of extreme weather events.

The challenge of farming in an uncertain climate

Weather forecasting systems have improved in accessibility and reliability over the last twenty years but the major issue for farming is anticipating how reliable the forecast will be in both the short and long term. For example, over the last two autumns, winter wheat establishment decisions have been a very fine balance between delaying drilling for blackgrass control and risking wet seedbeds and poor establishment conditions as seedbeds turned from very dry to prolonged waterlogging in a matter of a few days.

Advances in wheat production

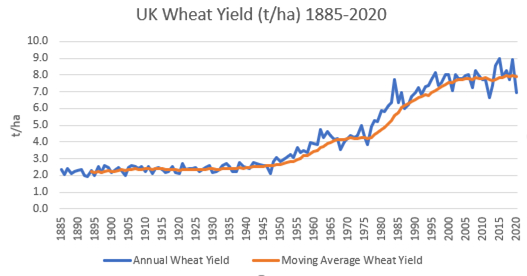

After grass, wheat is the most commonly grown crop in the UK accounting for about 2 million hectares of the 6.1 million hectares of croppable land. The UK is really well suited to growing wheat despite having just lost the World record wheat yield at 17.398t/ha to New Zealand. Many advances have been made in wheat yields over the last 50 years through genetics, management, and mechanisation. Average wheat yields hovering around 2.4t/ha for the early part of the 20th century but then rose quickly with the adoption of dwarf varieties, introduced in the Green Revolution, which could then be intensively managed. First of all, herbicides were adopted to remove competition from weeds and then fungicides were widely applied to help maintain yield in the lusher canopies which could be achieved by synthetic nitrogen applications. Towards the end of the 20th century, wheat yields were stable at around 7.7t/ha but have since failed to break the 8t/ha average.

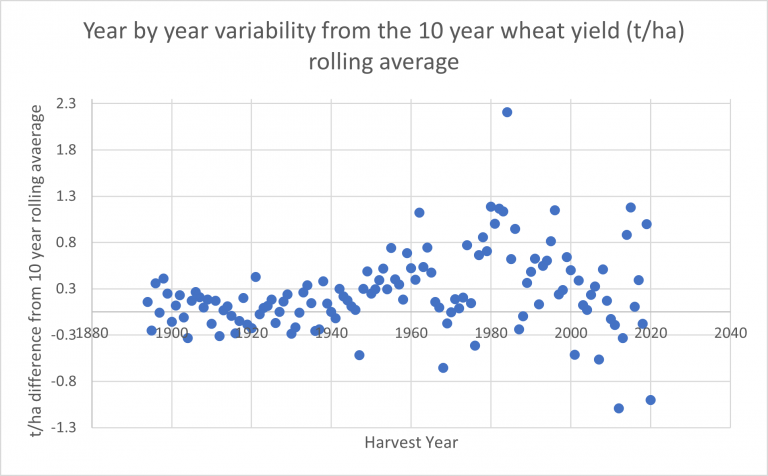

Data from Defra statistics

When the data is further interrogated it becomes quite clear that the amount of variability in yield has increased over the last 20 years making it harder for budgeting and cash flow. In the early 20th century, yields rarely fluctuated by more than 0.3t/ha whilst, over the last 20 years, fluctuations of 1.3t/ha have been commonly experienced.

Many farmers believe that these fluctuations are managed by variability in grain prices, however, the price of grain is determined by many global policies and political drivers as well as the impacts of extreme weather conditions. Therefore, the UK can suffer a poor harvest and the global grain price can still be low if global grain stocks are sufficient and cropping outlooks for the global major commodities are buoyant.

How extreme weather impacts yield

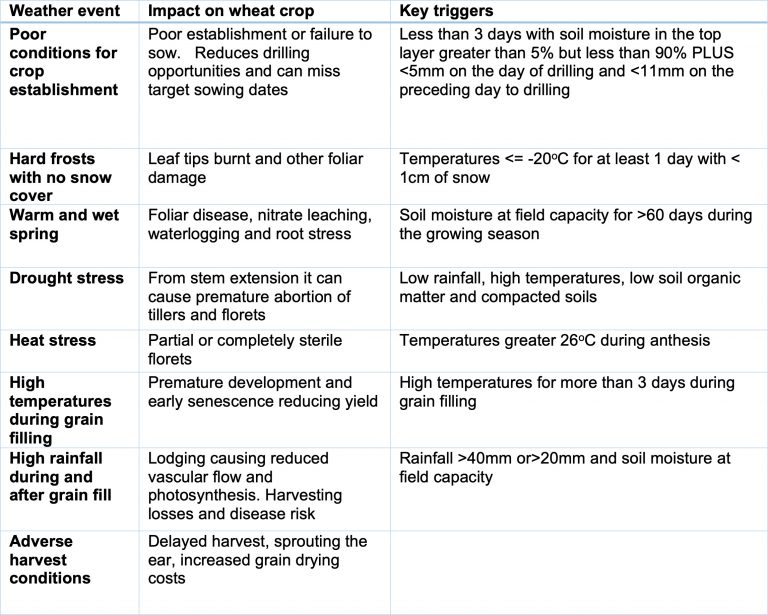

Extreme weather conditions normally cause a reduction in the yield of wheat regardless of when it occurs in the growing season. See the table for a range of extreme weather events which can severely impact yield and the impact they have on plant growth.

The UK climate projections predict warmer, wetter winters, and hotter, drier summers, alongside increased frequency and intensity of extremes. Temperatures in the last decade were already 1oC above pre-industrial levels recorded in 1850-1900 which may explain some of the greater variation observed in annual wheat yields. These changing weather patterns have already been influencing farm operations with challenging autumn establishment conditions and often delayed pre-emergence herbicide applications turning into a less effective peri or post emergence application, wet springs limiting early access to land and keeping soils colder for longer. On top of this, spring droughts have been experienced either early in the growing season, e.g. 2020, or later, e.g. 2018, which have impacted nitrogen applications and fungicide programmes due to the uncertainty of future yield potential and disease threat.

On top of the climate challenge, loss of active ingredients is also altering crop protection options from the neonicotinoid ban through to the loss of chlorothalonil, a cheap multi-site fungicide. Further withdrawals are currently occurring, e.g. epoxiconazole, and other products will be withdrawn in line with legislation (Active Substance Approval EC 1107/2009, Water Framework Directive (WFD) 2000/60 / EC (and related legislation such as the Drinking Water Directive and the Groundwater Directive) , Conditions of Approval of Neonicotinoids, Regulation 485/2013) resulting in the withdrawal of existing active substances and restrictions of the development of new pesticides and plant protection products. As well as legislative withdrawal, many are becoming less effective as the UK has wide scale herbicide, fungicide, and insecticide resistance issues which further limit the number of active ingredients which will successfully enhance crop yields.

Techniques to manage yield variations

There are several techniques that farmers can adopt to try and reduce the risk of yield variations and the resulting impact on cash flow including:

- Increasing diversity within the crop rotation so the risk of an extreme weather events is managed by reducing the amount of cropped area susceptible to damage during a key sensitive period.

- Changing machinery and labour to have more equipment available to work during key weather windows. However, increasing the size of machinery can sometimes further increase risk due to increased implement weight. Also, single pass equipment can become clogged up during field operations in marginal conditions or create large amounts of dust resulting in soil loss in dry periods.

- Stabilising and/or increasing organic matter is a priority as much arable land in the UK has suffered soil degradation over the last 60 years linked to increased crop demands to sustain higher yields, changing farming practices and extreme weather events. Soil organic matter and soil health has declined on many farms leading to less resilience within the farming system. Management techniques should be adopted to enhance soil organic matter and improve soil health and these could include incorporating straw, using FYM, reducing the intensity of tillage operations, adding a restorative diverse grass ley into the crop rotation whilst taking steps to avoid and correct compaction or nutritional issues throughout the soil profile.

- Buying crop shortfall insurance, such as that offered by Lycetts, which tracks the regional yield and pays out if the yield for the insured year is 10% below the average of the rolling average yield for the previous 8 years.

- Zoning the cropping area on the farm into high, medium and low risk zones for extreme weather events and evaluating stewardship or Biodiversity Net Gain opportunities for the high-risk areas. However, the problem occurs where the areas which are high risk for drought (shallow and light soils) are often the low risk areas for crop establishment challenges where high clay content soils can be difficult for establishing crops.

Overall, our climate is changing and as agriculture is so heavily impacted by the weather before and during the growing season and at harvest; it is vital that a range of steps are taken to try and protect against the risk of low yield. Whilst this article is primarily about wheat, the same challenges are being faced in other cereals, oilseed rape, and legume crops. Strategies for mitigating farming systems to adapt to climate change or to alleviate the risks include diversifying farming systems, insuring with crop shortfall insurance, improving soil health and organic matter on the farm and understanding the risk factors on crop yield.

Looking ahead to help plan and avoid the challenges of an uncertain climate and extreme weather events

Winter wheat severely challenged by yellow rust at ear emergence which will probably result in 30% yield loss

Patchy establishment with uncontrolled blackgrass due to poor autumn drilling conditions

Rutting caused by applying early nitrogen to promote tillering in wet conditions

Soil erosion caused by over cultivating down the slope on vulnerable soils, late drilling followed by a wet winter

Soil erosion due to poor establishment, compaction and excessive winter rainfall